We’re accustomed to the fact that much archaeology is collaborative in nature: we work with and rely on the work of others all the time to achieve our archaeological ends. However, what we overlook is the way in which much of what we do as archaeologists is dependent upon invisible collaborators – people who are absent, distanced, even disinterested. And these aren’t archaeologists working remotely and accessing the same virtual research environment as us in real time, although some of them may be archaeologists who developed the specialist software we have chosen to use. The majority of these are people we will never know, cannot know, who themselves will be ignorant of the context in which we have chosen to apply their products, and indeed, to compound things, will generally be unaware of each other. They are, quite literally, the ghosts in the machine.

We’re accustomed to the fact that much archaeology is collaborative in nature: we work with and rely on the work of others all the time to achieve our archaeological ends. However, what we overlook is the way in which much of what we do as archaeologists is dependent upon invisible collaborators – people who are absent, distanced, even disinterested. And these aren’t archaeologists working remotely and accessing the same virtual research environment as us in real time, although some of them may be archaeologists who developed the specialist software we have chosen to use. The majority of these are people we will never know, cannot know, who themselves will be ignorant of the context in which we have chosen to apply their products, and indeed, to compound things, will generally be unaware of each other. They are, quite literally, the ghosts in the machine.

Author: Jeremy Huggett

Re-visualising Visualisation

Visualisation is much in vogue at present, especially with the increasing availability and accessibility of virtual reality devices such as the Occulus Rift and the HTC Vive, plus cheaper consumer alternatives including the Google Daydream and Sony’s Playstation VR, and there’s always Google Cardboard. We’re told that enhancing our virtual senses will increase knowledge, especially when we move into a virtual world in which we are interconnected with others (e.g. Martinez 2016), and the future is anticipated to bring sensors that go beyond vision and hearing and transmit movement, smells, and textures.

Visualisation is much in vogue at present, especially with the increasing availability and accessibility of virtual reality devices such as the Occulus Rift and the HTC Vive, plus cheaper consumer alternatives including the Google Daydream and Sony’s Playstation VR, and there’s always Google Cardboard. We’re told that enhancing our virtual senses will increase knowledge, especially when we move into a virtual world in which we are interconnected with others (e.g. Martinez 2016), and the future is anticipated to bring sensors that go beyond vision and hearing and transmit movement, smells, and textures.

Hyperbole aside, we generally recognise (even if our audiences might not) that our archaeological digital visualisations are interpretative in nature, although how (or whether) we incorporate this in the visualisation is still a matter of debate. However, we understand that the data we base our visualisations upon are all too often incomplete, ambiguous, equivocal, contradictory, and potentially misleading whether or not we choose to represent this explicitly within the visualisation. I won’t rehearse the arguments about authority, authenticity etc. here (see Jeffrey 2015, Watterson 2015, Frankland and Earl 2015 (pdf), amongst others).

Gatekeepers in Digital Archaeology

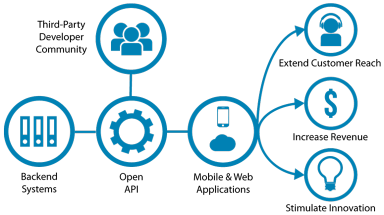

We’re becoming increasingly accustomed to our digital technologies acting as gatekeepers – perhaps most obviously in the way that the smartphone acts as gatekeeper to our calendar and/or email. In fact, this technological gatekeeping functionality appears everywhere you look, whether it’s in the form of physical devices providing access to information, software interfaces providing access to tools, or web interfaces providing access to data, for example. A while ago, I mused about the way that archaeological data are increasingly made available via key gatekeepers, and that consequently “negotiating access is often not as straightforward or clear-cut as it might be – both in terms of the shades of ‘openness’ on offer and the restrictions imposed by the interfaces to those data.” Since writing that, I’ve essentially left that statement hanging. What was I thinking of?

We’re becoming increasingly accustomed to our digital technologies acting as gatekeepers – perhaps most obviously in the way that the smartphone acts as gatekeeper to our calendar and/or email. In fact, this technological gatekeeping functionality appears everywhere you look, whether it’s in the form of physical devices providing access to information, software interfaces providing access to tools, or web interfaces providing access to data, for example. A while ago, I mused about the way that archaeological data are increasingly made available via key gatekeepers, and that consequently “negotiating access is often not as straightforward or clear-cut as it might be – both in terms of the shades of ‘openness’ on offer and the restrictions imposed by the interfaces to those data.” Since writing that, I’ve essentially left that statement hanging. What was I thinking of?

Deep-fried archaeological data

I’ve borrowed the idea of ‘deep-fried data’ from the title of a presentation by Maciej Cegłowski to the Collections as Data conference at the Library of Congress last month. As an archaeologist living and working in Scotland for 26 years, the idea of deep-fried data spoke to me, not least of course because of Scotland’s culinary reputation for deep-frying anything and everything. Deep-fried Mars bars, deep-fried Crème eggs, deep-fried butter balls in Irn Bru batter, deep-fried pizza, deep-fried steak pies, and so it goes on (see some more not entirely serious examples).

Hardened arteries aside, what does deep-fried data mean, and how is this relevant to the archaeological situation? In fact, you don’t have to look too hard to see that cooking is often used as a metaphor for our relationship with and use of data.

Unravelling Cyberinfrastructures

Infrastructures are all around us. They make the modern world work – whether we’re thinking of infrastructures in terms of gas, electric or water supply, telephony, fibre networks, road and rail systems, or organisations such as Google, Amazon and others, and so on. Infrastructures are also what we are building in archaeology. Data distribution systems have increasingly become an integral part of the archaeological toolkit, and the creation of a digital infrastructure – or cyberinfrastructure – underpins the set of grand challenges for archaeology laid out by Keith Kintigh and colleagues (2015), for example. But what are the consequences and challenges associated with these kinds of infrastructures? What are we knowingly or unknowingly constructing?

Patrik Svensson (2015) has pointed to a lack of critical work and an absence of systemic awareness surrounding the developments of infrastructures within the humanities. While he points to archaeology as one of the more developed in infrastructural terms, this isn’t necessarily a ‘good thing’ in the light of his critique. As he says, “Humanists do not … necessarily think of what they do as situated and conditioned in terms of infrastructures” (2015, 337) and consequently:

“A real risk … is that new humanities infrastructures will be based on existing infrastructures, often filtered through the technological side of the humanities or through the predominant models from science and engineering, rather than being based on the core and central needs of the humanities.” (2015, 337).

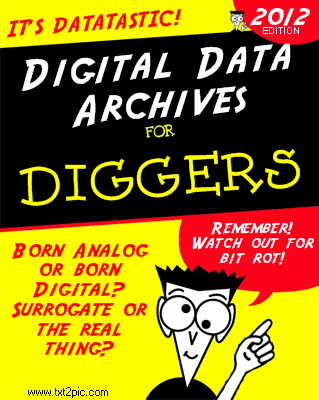

A Digital Afterlife

Solutions to the crisis in archaeological archives in an environment of shrinking resources often involve selection and discard of the physical material and an increased reliance on the digital. For instance, several presentations to a recent day conference on Selection, De-selection and Rationalisation organised by the Archaeological Archives Group implicitly or explicitly refer to the effective replacement of physical items with data records, where either deselected items were removed from the archive or else material was never selected for inclusion in the first place because of its perceived ‘low research potential’. Indeed, Historic England are currently tendering for research into what they call the ‘rationalisation’ of museum archaeology collections

Solutions to the crisis in archaeological archives in an environment of shrinking resources often involve selection and discard of the physical material and an increased reliance on the digital. For instance, several presentations to a recent day conference on Selection, De-selection and Rationalisation organised by the Archaeological Archives Group implicitly or explicitly refer to the effective replacement of physical items with data records, where either deselected items were removed from the archive or else material was never selected for inclusion in the first place because of its perceived ‘low research potential’. Indeed, Historic England are currently tendering for research into what they call the ‘rationalisation’ of museum archaeology collections

“… which ensures that those archives that are transferred to museums contain only material that has value, mainly in the potential to inform future research.” (Historic England 2016, 2)

Historic England anticipate that these procedures may also be applied retrospectively to existing collections. It remains too early to say, but it seems more than likely a key approach to the mitigation of such rationalisation will be the use of digital records. In this way, atoms are quite literally converted into bits (to borrow from Nicholas Negroponte) and the digital remains become the sole surrogate for material that, for whatever reason, was not considered worthy of physical preservation. What are the implications of the digital coming to the rescue of the physical archive in this way?

Looking for explanations

In 2014 the European Union determined that a person’s ‘right to be forgotten’ by Google’s search was a basic human right, but it remains the subject of dispute. If requested, Google currently removes links to an individual’s specific search result on any Google domain that is accessed from within Europe and on any European Google domain from wherever it is accessed. Google is currently appealing against a proposed extension to this which would require the right to be forgotten to be extended to searches across all Google domains regardless of location, so that something which might be perfectly legal in one country would be removed from sight because of the laws of another. Not surprisingly, Google sees this as a fundamental challenge to accessibility of information.

As if the ‘right to be forgotten’ was not problematic enough, the EU has recently published its General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 to be introduced from 2018 which places limits on the use of automated processing for decisions taken concerning individuals and requires explanations to be provided where an adverse effect on an individual can be demonstrated (Goodman and Flaxman 2016). This seems like a good idea on the face of it – shouldn’t a self-driving car be able to explain the circumstances behind a collision? Why wouldn’t we want a computer system to explain its reasoning, whether it concerns access to credit or the acquisition of an insurance policy or the classification of an archaeological object?

Digital Data Realities

The UK is suddenly wakening from the reality distortion field that has been created by politicians on both sides and only now beginning to appreciate the consequences of Brexit – our imminent departure from the European Union. But – without forcing the metaphor – are we operating within some kind of archaeological reality distortion field in relation to digital data?

Undoubtedly one of the big successes of digital archaeology in recent years has been the development of digital data repositories and, correspondingly, increased access to archaeological information. Here in the UK we’ve been fortunate enough to have seen this develop over the past twenty years in the shape of the Archaeology Data Service, which offers search tools, access to digital back-issues of journals, monograph series and grey literature reports, and the availability of downloadable datasets from a variety of field and research projects. In the past, large-scale syntheses took years to complete (for instance, Richard Bradley’s synthesis of British and Irish prehistory took four years paid research leave with three years of research assistant support in order to travel the country to seek out grey literature reports accumulated over 20 years (Bradley 2006, 10)). At this moment, there are almost 38,000 such reports in the Archaeology Data Service digital library, with more are added each month (a more than five-fold increase since January 2011, for example). The appearance of projects of synthesis such as the Rural Settlement of Roman Britain is starting to provide evidence of the value of access to such online digital resources. And, of course, other countries increasingly have their own equivalents of the ADS – tDAR and OpenContext in the USA, DANS in the Netherlands, and the Hungarian National Museum’s Archaeology Database, for instance).

But all is not as rosy in the archaeological digital data world as it might be.

Biggish Data

Big Data is (are?) old hat … Big Data dropped off Gartner’s Emerging Technologies Hype Cycle altogether in 2015, having slipped into the ‘Trough of Disillusionment’ in 2014 (Gartner Inc. 2014, 2015a). The reason given for this was simply that it had evolved and had become the new normal – the high-volume, high-velocity, high-variety types of information that classically defined ‘big data’ were becoming embedded in a range of different practices (e.g. Heudecker 2015).

At the same time, some of the assumptions behind Big Data were being questioned. It was no longer quite so straightforward to claim that ‘big data’ could overcome ‘small data’ by throwing computer power at a problem, or that quantity outweighed quality such that the large size of a dataset offset any problems of errors and inaccuracies in the data (e.g. Mayer-Schönberger and Cukier 2013, 33), or that these data could be analysed in the absence of any hypotheses (Anderson 2008).

For instance, boyd and Crawford had highlighted the mythical status of ‘big data’; in particular that it somehow provided a higher order of intelligence that could create insights that were otherwise impossible, and assigned them an aura of truth, objectivity and accuracy (2012, 663). Others followed suit. For example, McFarland and McFarland (2015) have recently shown how most Big Data analyses give rise to “precisely inaccurate” results simply because the sample size is so large that they give rise to statistically highly significant results (and hence the debacle over Google Flu Trends – for example, Lazer and Kennedy 2015). Similarly, Pechenick et al (2015) showed how, counter-intuitively, results from Google’s Books Corpus could easily be distorted by a single prolific author, or by the fact that there was a marked increase in scientific articles included in the corpus after the 1960s. Indeed, Peter Sondergaard, a senior vice president at Gartner and global head of Research, underlined that data (big or otherwise) are inherently dumb without algorithms to work on them (Gartner Inc. 2015b). In this regard, one might claim Big Data have been superseded by Big Algorithms in many respects.

Let’s talk about digital archaeology

Andre Costopoulos lays down a series of provocations in his opening editorial for the new Digital Archaeology section of the Frontiers in Digital Humanities journal. So far, there doesn’t seem to have been much response – Twitter chatter, for example, simply draws attention to the article without comment (except perhaps in one instance where it may or may not be addressed tongue-in-cheek – such is the danger of social media!).

He starts by saying simply:

“I want to stop talking about digital archeology. I want to continue doing archeology digitally … I would like to lay the groundwork for the journal as a place primarily to do archeology digitally, rather than as a place to discuss digital archeology”.

There’s certainly nothing wrong about a journal focussed on digital archaeological applications, but what’s wrong with talking about digital archaeology? He goes on: