Nicholas Carr points to a new essay by Leon Wieseltier, former literary editor at The New Republic recently moved to The Atlantic, on the state of culture in the digital age. It’s a wide-ranging commentary on the impact of technology on culture:

“… words cannot wait for thoughts, and first responses are promoted into best responses, and patience is a professional liability. As the frequency of expression grows, the force of expression diminishes …”.

He talks of the way that information and knowledge have become treated as equal or equivalent, and the expectation that knowledge requires a scientific approach and so as a consequence the humanities are viewed as less relevant. He argues that we have shifted away from a worldview where humanity is at the centre of our universe to one in which impersonal forces – technologies – have become the key determinant.

Consequently, he believes that thinking about the role of technology in daily life is critically important:

“We are still in the middle of the great transformation, but it is not too early to begin to expose the exaggerations, and to sort out the continuities from the discontinuities … Every technology is used before it is completely understood. There is always a lag between an innovation and the apprehension of its consequences. We are living in that lag, and it is a right time to keep our heads and reflect.”

He goes on to warn that:

“questions of quality on the new [technological] platforms should be no different from questions of quality on the old platforms. Otherwise a quantitative expansion will result in a qualitative contraction. The new devices do not in themselves authorize a revision of the standards of evidence and argument and style that we championed in the old devices.”

As a result, he proposes that technologies may be more neutral about their use than is often proposed – that they are “simply new means for old ends”. So having set up an argument characterising the transformative effects of digital technologies and the way that people are caught up in the rush of the new and the now, he steps back and offers the comfort that essentially things won’t change unless we let them, in spite of the fact that the evidence suggests otherwise – that we don’t have the level of control and influence that this would imply. Indeed, nor are the technologies neutral, empty vessels: in one way or another they have designed within them the requirements to restructure or remodel the information that goes into them and hence tend to influence applications and outcomes. He reassuringly suggests that we will still need our humanistic methods to make sense of the deluge of information derived from the cyberinfrastructures we build, but overlooks the drive amongst technologists to automate even (especially?) these processes of analysis and understanding that follow from discovery and extraction.

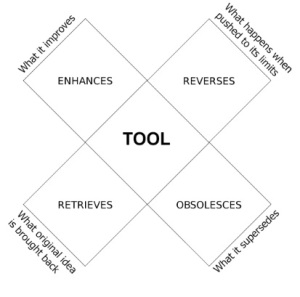

Critical thinking about the role of technology is – as he argues – both timely and vitally important. While there is undoubtedly a sense in which new technologies provide new means for old ends, it is not as simple as this, as Marshall McLuhan pointed out almost forty years ago in his ‘Laws of Media’. These ‘laws’ were defined by McLuhan as exploratory tools for providing insights into the effects of technology through the consideration of:

- Amplification: what aspects of human function does it enhance or amplify?

- Obsolescence: what does it eclipse or supersede that had previously been extensively used?

- Retrieval: what was previously obsolescent but now comes back into use?

- Reversal: what does it reverse or flip into when developed to its full potential?

(McLuhan 1977, 175 and see Huggett 2012, 210ff).

One of the benefits of these oppositions is the way in which they can combine to balance the utopian/dystopian perspectives that frequently accompany the consideration of technologies: the potential for utopianism in discussing enhancement or amplification is offset to some degree by the potential for dystopianism in discussing obsolescence, for instance. It’s a balance that’s all-too-hard to achieve, let alone maintain, and in many respects, Wieseltier’s essay combines both, but lacks the balance.

Wieseltier argues that:

“The burden of proof falls on the revolutionaries, and their success in the marketplace is not sufficient proof. Presumptions of obsolescence, which are often nothing more than the marketing techniques of corporate behemoths, need to be scrupulously examined.”

This is equally true In the case of digital archaeology, although perhaps the pressures are more to do with justifying research grants and responding to political pressures than marketing techniques per se – and while success is certainly no measure of value, surely the burden of proof is one to be shared rather than left in the hands of the proponents of these technologies if this technological critique is to have any meaning?

References

Huggett, J. (2012) What lies beneath: lifting the lid on archaeological computing. In: Chrysanthi, A., Murrietta Flores, P. and Papadopoulos, C. (eds.) Thinking Beyond the Tool: Archaeological Computing and the Interpretative Process. Archaeopress, pp. 204-214. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/61333/

McLuhan, M. 1977. ‘Laws of the media’, Et cetera 34 (2), 173-179.

Wieseltier, L. 2015. ‘Among the Disrupted’, Sunday Book Review (New York Times January 18th, 2015). http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/18/books/review/among-the-disrupted.html