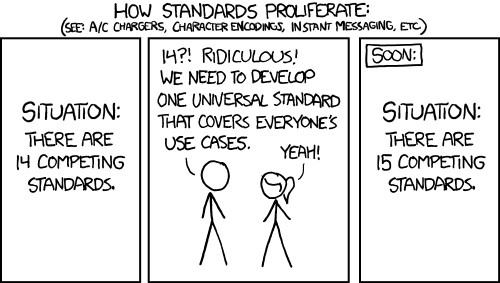

Putting aside the hype associated with artificial intelligence (and generative AI in particular), there’s a great deal of talk surrounding the application of AI within archaeology with numerous examples of AI approaches to automated classification, feature recognition, image analysis, and so on. But much of it seems fairly uncritical – perhaps because it is largely associated with exploratory and experimental approaches seeking to find a place for AI, although there is also something of a publication/presentation bias favouring positive outcomes (e.g., see Sobotkova et al. 2024, 7). AI is typically presented as offering greater efficiencies and productivity gains, and any negative effects, where noted, can be managed out of the equation. In many respects this conforms to the broader context of AI where it is often seen as possessing an almost mythical, ideological status, sold by large organisations as the solution to everything from overflowing mailboxes to the climate crisis.

Cobb’s survey of generative AI in archaeology (Cobb 2023) focusses on key application areas where genAI may be of meaningful use: research (e.g., Spenneman 2024), writing, illustration (e.g., Magnani and Clindaniel 2023), teaching, and programming (e.g., Ciccone 2024), although Cobb sees programming as the most useful with mixed results elsewhere. However, Spenneman (2024, 3602-3) predicts that genAI will affect how cultural heritage is documented, managed, practiced, and presented, primarily through its provision of analysis and decision-making tools. Likewise, Magnani and Clindaniel (2023, 459) boldly declare genAI to be a powerful illustrative tool for depicting and interpreting the past, enabling multiple perspectives and reinterpretations, but at the same time, admit that