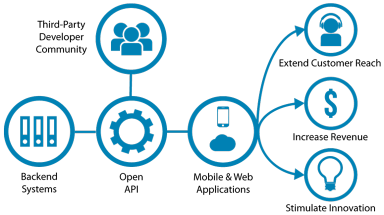

We’re becoming increasingly accustomed to our digital technologies acting as gatekeepers – perhaps most obviously in the way that the smartphone acts as gatekeeper to our calendar and/or email. In fact, this technological gatekeeping functionality appears everywhere you look, whether it’s in the form of physical devices providing access to information, software interfaces providing access to tools, or web interfaces providing access to data, for example. A while ago, I mused about the way that archaeological data are increasingly made available via key gatekeepers, and that consequently “negotiating access is often not as straightforward or clear-cut as it might be – both in terms of the shades of ‘openness’ on offer and the restrictions imposed by the interfaces to those data.” Since writing that, I’ve essentially left that statement hanging. What was I thinking of?

We’re becoming increasingly accustomed to our digital technologies acting as gatekeepers – perhaps most obviously in the way that the smartphone acts as gatekeeper to our calendar and/or email. In fact, this technological gatekeeping functionality appears everywhere you look, whether it’s in the form of physical devices providing access to information, software interfaces providing access to tools, or web interfaces providing access to data, for example. A while ago, I mused about the way that archaeological data are increasingly made available via key gatekeepers, and that consequently “negotiating access is often not as straightforward or clear-cut as it might be – both in terms of the shades of ‘openness’ on offer and the restrictions imposed by the interfaces to those data.” Since writing that, I’ve essentially left that statement hanging. What was I thinking of?

Tag: open data

Unravelling Cyberinfrastructures

Infrastructures are all around us. They make the modern world work – whether we’re thinking of infrastructures in terms of gas, electric or water supply, telephony, fibre networks, road and rail systems, or organisations such as Google, Amazon and others, and so on. Infrastructures are also what we are building in archaeology. Data distribution systems have increasingly become an integral part of the archaeological toolkit, and the creation of a digital infrastructure – or cyberinfrastructure – underpins the set of grand challenges for archaeology laid out by Keith Kintigh and colleagues (2015), for example. But what are the consequences and challenges associated with these kinds of infrastructures? What are we knowingly or unknowingly constructing?

Patrik Svensson (2015) has pointed to a lack of critical work and an absence of systemic awareness surrounding the developments of infrastructures within the humanities. While he points to archaeology as one of the more developed in infrastructural terms, this isn’t necessarily a ‘good thing’ in the light of his critique. As he says, “Humanists do not … necessarily think of what they do as situated and conditioned in terms of infrastructures” (2015, 337) and consequently:

“A real risk … is that new humanities infrastructures will be based on existing infrastructures, often filtered through the technological side of the humanities or through the predominant models from science and engineering, rather than being based on the core and central needs of the humanities.” (2015, 337).

Digital Data Realities

The UK is suddenly wakening from the reality distortion field that has been created by politicians on both sides and only now beginning to appreciate the consequences of Brexit – our imminent departure from the European Union. But – without forcing the metaphor – are we operating within some kind of archaeological reality distortion field in relation to digital data?

Undoubtedly one of the big successes of digital archaeology in recent years has been the development of digital data repositories and, correspondingly, increased access to archaeological information. Here in the UK we’ve been fortunate enough to have seen this develop over the past twenty years in the shape of the Archaeology Data Service, which offers search tools, access to digital back-issues of journals, monograph series and grey literature reports, and the availability of downloadable datasets from a variety of field and research projects. In the past, large-scale syntheses took years to complete (for instance, Richard Bradley’s synthesis of British and Irish prehistory took four years paid research leave with three years of research assistant support in order to travel the country to seek out grey literature reports accumulated over 20 years (Bradley 2006, 10)). At this moment, there are almost 38,000 such reports in the Archaeology Data Service digital library, with more are added each month (a more than five-fold increase since January 2011, for example). The appearance of projects of synthesis such as the Rural Settlement of Roman Britain is starting to provide evidence of the value of access to such online digital resources. And, of course, other countries increasingly have their own equivalents of the ADS – tDAR and OpenContext in the USA, DANS in the Netherlands, and the Hungarian National Museum’s Archaeology Database, for instance).

But all is not as rosy in the archaeological digital data world as it might be.

Open data and the transformation of archaeological knowledge

[To interrupt the blogging hiatus, here’s the introduction to a recently published paper …]

Since the mid-1990s the development of online access to archaeological information has been revolutionary. Easy availability of data has changed the starting point for archaeological enquiry and the openness, quantity, range and scope of online digital data has long since passed a tipping point when online access became useful, even essential. However, this transformative access to archaeological data has not itself been examined in a critical manner. Access is good, exploitation is an essential component of preservation, openness is desirable, comparability is a requirement, but what are the implications for archaeological research of this flow – some would say deluge – of information?

Since the mid-1990s the development of online access to archaeological information has been revolutionary. Easy availability of data has changed the starting point for archaeological enquiry and the openness, quantity, range and scope of online digital data has long since passed a tipping point when online access became useful, even essential. However, this transformative access to archaeological data has not itself been examined in a critical manner. Access is good, exploitation is an essential component of preservation, openness is desirable, comparability is a requirement, but what are the implications for archaeological research of this flow – some would say deluge – of information?

Unconscious Bias

My employer has decided to send all those of us involved in recruitment and promotion on Unconscious Bias training, in recognition that unconscious bias may affect our decisions in one way or another. Unconscious bias in our dealings with others may be triggered by both visible and invisible characteristics, including gender, age, skin colour, sexual orientation, (dis)ability, accent, education, class, professional group etc.. That started me thinking – what about unconscious bias in relation to digital archaeology?

‘Unconscious bias’ isn’t a term commonly encountered within archaeology, although Sara Perry and others have written compellingly about online sexism and abuse experienced in academia and archaeology (Perry 2014, Perry et al 2015, for example). ‘Bias’, on the other hand, is rather more frequently referred to, especially in the context of our relationship to data. Most of us are aware, for instance, that as archaeologists we bring a host of preconceptions, assumptions, as well as cultural, gender and other biases to bear on our interpretations, and recognising this, seek means to reduce if not avoid it altogether. Nevertheless, there may still be bias in the sites we select, the data we collect, and the interpretations we place upon them. But what happens when the digital intervenes?

What do we want from Open?

Some rather random thoughts about open data, open source, open access in archaeology from a recent interview for OpenScience …

http://openscience.com/jeremy-huggett-davide-tanasi-want-open/

Legibility, agency, and negotiability

There’s a lot of debate in the wider world about digital data – issues of access and privacy, the case of Aaron Swartz and open access to knowledge, the Ed Snowden revelations, and, at the personal level, the way that we all leave data trails behind as we traverse the Internet. Surrendering our personal data is difficult to avoid, even if we forswear Facebook, Google, and their like who build their business models on their ability to capture data about us.

In a recent paper by Richard Mortier et al, (2015), they argue that this new world of data requires a new kind of study of human-data interaction, looking at the implications of the data we generate in all kinds of different ways, knowingly or unknowingly.

Changing gear

There’s an interesting project run out of Durham and Newcastle Universities by Bob Simpson and Robin Humphrey, Writing Across Boundaries, which started off as a series of workshops to look at challenges faced by researchers writing a thesis employing qualitative data but has broadened out somewhat thereafter. Simpson and Humphrey suggest that in recent years

“there has been acceleration in the way researchers progress from one kind of writing to another – doctoral thesis to articles to monograph to more accessible forms of dissemination. The pressure to do in couple of years what an earlier generation might have done in a couple of decades has a variety of external drivers. These mostly come down to funding and the competition for scarce resources on the one hand, and the demonstration of public accountability on the other.”

Big Data and Distance

One of the features of the availability of increasing amounts of archaeological data online is that it frequently arrives without an accompanying awareness of context. Far from being a problem, this is often seen as an advantage in relation to ‘big data’ – indeed, Chris Anderson has claimed that context can be established later once statistical algorithms have found correlations in large datasets that might not otherwise be revealed.

Continue reading

Open Data quality

In relation to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) database, David Gill on his ‘Looting Matters’ blog has pondered “How far can we trust the information supplied with the reported objects? Are these largely reported or ‘said to be’ findspots?”.

Spatial information is frequently cited as a problem in relation to open archaeological data – but the focus tends to be on the risks it poses for looting (for example, Bevan 2012, 7-8; Kansa 2012, 508-9).